I found myself thinking about the Dark Souls trilogy, again. Maybe one day I won’t have to think about them again… here is my attempt at exorcising them. Okay. I’ll refer to them as 1, 2, and 3 here.

So the other day I wondered some things. In particular:

- I had meticulously (and wastefully) platinumed 3. Then why do I have little impression or sense of wonder when recalling it?

- Why does 2 stand out as the most fascinating and exciting in my mind, even if I only played through it once?

- Why despite 1’s first half being so strong, is it still not as memorable as 2?

I skimmed a speedrun of 3. It’s easy to see why it’s less memorable than 1 or 2. It has a fairly standard and safe art direction (undead decrepit stuff, dreary boring high fantasy). Environments out of that genre that don’t mystify me (sprawling castles, medieval villages in visually dense cliffs, swampy woods, European halls, catacombs…).

I can recall many of the spaces and levels in detail, but I don’t have the tinge of awe and jealousy I tend to get when being impressed.

Drawn in contrast to 2, some other reasons surface. 3 is far more world-design continuous (here on just continuous) than 2.

See the Appendix at the bottom for definitions of the terms I’ll use in this post – hyper-, normal-, semi-, and discontinuous. I’ll assume you sort of understand what I mean by these terms going forward:

Okay, so Dark Souls 3 – or just 3 – the game is split into three chunks – Castle, Forest, and Snow Castle. There is a break between Castle and Forest (where you fly, conveying a sense of descent into the world), and a break between Forest and Snow Castle that’s articulated by a level (catacombs, conveying a sense horizontal-plane traversal into the world). These chunks are nearly hypercontinuous within themselves – while they’re not open world, there are handfuls of mutual vantage points, things are detailed and realistically sized. (3’s three chunks are circled here:)

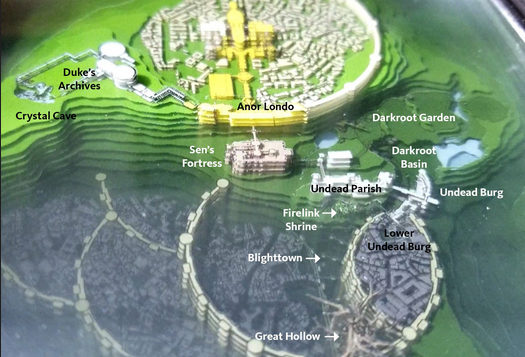

Dark Souls 1 is roughly similar to Dark Souls 3 in continuity, but it takes place in a vertically oriented world. We could pick apart definitions as to what extent these two are continuous, but my focus isn’t on those games. Still, this glass model by Twitter use @rigmarole111 captures 1’s world well: Notice that the game has four strata: the top-level areas – Anor Londo, Duke’s Archive, mid-level areas (Sen’s, Parish, Burg, Garden), lower-level areas (Blighttown), and subterranean areas (not pictured).

People love 1’s first half because you’re exploring the middle and lower-level areas, totally on your own, shrouded in mystery, and the game is good at helping you create connections between the world (as you play for the first time the structure is not at all obvious). The goal of the game is initially to reach Anor Londo, but you’ve got to explore all over before you get there, and many closed off/difficult paths will tempt you.

I would say 1 gestures at hyper-continuity at times, but actually some of its major mutual vantage points are faked (to good effect), and I would classify it as actually closer to normal-continuous. That is to say, none of its connections are confusing or baffling. If we are walking down, we’re going to the underground, and reach fire-y lava areas. If we go up, we go towards grand, royalty castle areas. It’s standard videogame world stuff (see any castlevania game), executed well in 3D.

Still… it’s not as inspiring as 2 to me. Why? By most popular accounts, 2 is a ‘mess’. The areas don’t make any sense, they connect randomly, there’s no ‘blog-worthy shortcuts!’.

Here’s a world map of Dark Souls 2, where I’ve highlighted the game’s paths.

A few notes:

- Everything spirals out from Majula, a seaside village.

- Game Structure:

- Collect 4 Important Things at the end of 4 paths, located in: Black Gulch (deep dark area), Iron Keep (fire castle in mountains), Brightstone cove (church/caves near a settlement near the ocean), and Sinner’s Rise (moonlit fortress near the sea)

- Visit Drangleic Castle, go deep deep down all the way to Undead Crypt

- Go way way up to Dragon Shrine

- End the game at Throne of Want (in the castle)

- There’s basically no crossover between main paths and there are barely any mutual vantage points

2 varies from 1 because 2’s world is representing an entire continent. There are little to no mutual vantage points because as you walk from one area to another – even without loading screens – you might be implied to travel miles. The player is going on a world-spanning adventure, much like a JRPG, just without the game giving us the abstraction of a world map to make that feel more coherent. We walk through a mysterious tunnel from Majula to Heide’s tower, and emerge 10 miles away. A quick trek through some woods and a small cave system shoots us out at a shore all the way at the other end of the world. An elevator at the top of a poisonous windmill takes us to a fire-y lava keep. And so on and so forth.

Because 2 is missing a world-map-esque abstraction layer, the game world inevitably connects in some confusing ways. Walking 100 meters can actually imply travelling all sorts of distances. Thus 2 has inconsistencies to how you travel between spaces, and it approaches being discontinuous, and thus becomes a semi-continuous game at times.

Back to Dark Souls 1: while playing, you are oriented within the world. Even as you uncover new places, you’re still aware, roughly, where you are vertically within the game’s world, and if you’re not aware (perhaps as you go to blighttown for the first time), a mutual vantage point (Great Swamp to Undead Burg) comes along and situates you within the world. Or if you wandered into Demon Ruins early and are disoriented, you’ll still become oriented once you see Demon Ruins from Tomb of the Giants.

As a player explores a game’s world, tension slowly builds as they sense they’ve drifted far from home, far from the familiar. And within this tension is where lack of continuity can be used to achieve various effects. Connect the player back to a familiar place and let them feel grounded. Or lead them further and further from the familiar, connecting areas in surprising ways.

2 doesn’t do anything to situate you within the island unless you go and look it up. It’s just one area after another, and the sense of endlessly going deeper into some fever dream of a continent. You just pick a random direction from Majula and keep going and going and going, and it feels like you may never reach any end point. You just know you’re either “sort of far” from Majula or “really far” from Majula.

Eventually, you do hit the end of a path, and the magic wears off, and you get one of the 4 magic items and go on to find the next.

This kind of semicontinuity is fascinating to me. It happens when a game establishes a consistent physical logic but then chooses to break its rules at certain times, or to at least not be consistent in one method of arranging the game’s world. Dark Souls 2 creates fairly continuous areas such as Forest of Fallen Giants, but at the same time does absurd things like having a well take you to a rat-infested catacomb, which THEN takes you to a poorly-lit cave with shambles of wooden housing, and finally some eerie, green cave. Nothing in the game really explains how this connects spatially to the rest of the game (unlike 1’s Lost Izalith, which you can see from elsewhere in the game). Instead, 2 is content to shove you from one area to the next. 2 feels like the randomness of some old videogames’ worlds, but expressed through a detailed 3D world with no loading screens. It’s full of interesting and inconsistent ideas, and like some Twitter mutuals put it – feels like playing a romhack of Dark Souls.

2 is the most memorable for these reasons. You take an elevator down from the top of a castle, and for some reason it shoots you out into a sprawling, blue, underground lake:

And if that wasn’t enough, there’s another elevator which takes you to an underground crypt.

In another section, a mansion sits off the side of a road: you then take the world’s tallest elevator up to a floating set of islands and dragon temples. Now, these strange transitions extremely memorable just because of how bizarre they are, peppered in between fairly reasonable transitions (e.g. walking through misty woods, to forested pathways, to some shady ruins). These moments are strange because the game has lots of non-strange transitions (like the interior of Drangleic Castle), and the game plays them both off as normal.

What semicontinuity gets at for me is the exciting ways we can represent our game worlds as designers. There’s no need to adhere to any one formula or idea: the ways areas are connected can be carefully thought through and become expressive.

It’s something we thought about while making Anodyne 2: Return to Dust (Spoilers ahead.. if you quit Anodyne 2 after 1 hour this is a good time to go finish it!!).

We initially establish a videogame-y logic to shrinking into people located in the 3D world, putting the game in the vicinity of normal-continuous. But as the game goes on, it’s revealed that the linkage of “3D character” and “2D world” is not always paired. Iwasaki Antimon takes you to a mailbox of a person Iwasaki obsesses over. The fur of a dog-creature ends up being a village you reside in for weeks. The desertnpc takes you to something completely unexpected. Pastel Horizon, Minorma’s Orb and New Theeland connect through an alternate Anodyne 1’s Nexus. The notions of space and how they should connect shift from a straightforward videogame-y premise to something disorienting and discontinuous. Anodyne 2’s continuity shifts as you get further… and it uses this to suggest a certain location in 2D as further away.

These sorts of formalized techniques can be used hand-in-hand with the story themes to make certain ideas resonate stronger with the player. For example, putting Dustbound Village inside a nano area makes you wonder about the rest of the 2D worlds you’ve visited – and gets you to rethink what you’ve learned about your role as a Nano Cleaner in Anodyne 2’s world. The strange large areas in the Outer Sands break down an attempt at a ‘logical’ understanding of Anodyne 2’s world’s fabric and suggests something that exists on a more fantastical layer. Thinking about and using continuity in different ways can create different headspaces for a player to inhabit as they read what you’ve written or prepared for them to play through.

Anyways, all degrees of continuity can result in interesting games. On the hypercontinuous end, we could have an exploration of a single bedroom, not necessarily sprawling and repetitive corpgames. Or an exploration of a single town (like in Attack of the Friday Monsters). There’s no right approach to making games or picking the level of continuity. But if you’re designing games it’s good to find some approach that you care about.

Appendix on defining continuous/etc

As always, game design theory is… sort of made up, right? These ideas may bear fruit when analyzing certain games, they may be worthless for others.

I’ll define continuity as a game’s tendency to have unbroken, realistically-sized spaces that you travel through without many cuts. On one end of the spectrum, games can be hypercontinuous (painful accuracy to real life – exteriors of buildings always match the interiors, the camera never cuts, there is no fast travel). I don’t know of many large games that are hypercontinuous, but the majority of recent open-world corporate games (corpgames) are close to this (Breath of the Wild, God of War, Grand Theft Auto).

Or games can be discontinuous – levels connect with seemingly no underlying logic (Yume Nikki, Goblet Grotto, Chameleon Kid).

But most games tend to lay in the middle – normal-continuous. This is when a game employs the standard set of breaks in its spatial traversal that we expect: a JRPG brings you from a world map (abstract) to various towns and dungeons. We traverse the world both concretely (through dungeons and towns) but also abstractly, through a world map. However, to the player, it’s always understood where you are in this world and the game generally intends its world to be remembered as a continuous space, even if it may change the level of abstraction from time to time. Normal-continuous represents what today’s commonly accepted practices are in terms of how a game articulates its transitions from one area to another.

Hypercontinuous

- Characterized by a game whose spaces have an experience of moving about them that is very close to real life.

- Likely to not have restricted levels (e.g. you can walk anywhere)

- Exists at big and small game scales: From “See that mountain? You can visit it!” to “spend a day sitting in an apartment.”

- Usually 3D, just because 2D more or less is always an abstraction from “realistic” representations of 3D space

Normal-Continuous

- Most games. E.g. JRPGs with world maps, visual novels with different areas

- Spaces may not be ‘realistic’ in representation or connection

- a player can make sense of where they are in the world most of the time, because areas are connected with consistent logic and the game makes an effort to let the player situate themselves (through a world map, etc.)

- travelling between areas is consistently represented and has consistent outcomes. E.g. when a game has 3D houses you can enter, if you enter the door and then always enter an interior area, the game is following its own rule that “Going into houses leads to an interior space”. A continuous game is unlikely to violate this rule. Other rules could be – Doors take you to new areas, doors take you to the same area if you re-use them, etc. A discontinious approach would be that sometimes a house’s door takes you to a beach or something

Semicontinuous

- Either a mixture of discontinous and normal/hyper-continuous approaches, intentionally (or not ) breaking ‘good practices’ and breaking the sense of logic to its game’s world

Discontinuous

If a game never situates its player in a familiar place, but shows one surprising locale after another, it enters the realm of discontinuous, like dream-exploration Yume Nikki, labyrinthian platformer Chameleon Kid, semi-procedurally-generated 0n0w (https://colorfiction.itch.io/0n0w) or spiraling 2D/3D maze 10 Beautiful Postcards (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=68N1udqRrvk) , or various early PC games that didn’t seem to ‘care’ about player’s navigation or “good practices”. Games that use this approach can explore unique feelings, sometimes terrifying. Digital space within discontinuous games can be implied to be infinite and unknowable, and that’s a very interesting situation to place a player into.

In choosing not to embody a place and be hypercontinuous, a discontinuous game begins to embody an abstract sense of feelings depending on the game, but also the game opens up more space for a player to relate *their* spatial memories with that of the games.

Anodyne 1 is somewhat discontinuous, by way of Yume Nikki’s influence. And I think it’s a big reason why many people remember its world and take away different things – in a discontinuous game world, a player is left to form many of their own associations based on what images and text the designer provides.

As a game changes its digital space from more realistically connected to more discontinous, the world may feel unknowable, a fever dream of unrelated parts and images that seem to go on endlessly, a fearsome nightmare or dream, all contained within a few bits on a computer’s hard drive…

(If you liked this post… I’m on Twitter! https://twitter.com/han_tani . I also run a discord for my game studio Analgesic Productions at https://discord.com/invite/analgesic

Or… join our studio’s newsletter and check out our games at https://analgesic.productions/!